February 02, 2011

For some Africans, southern Sudan's expected independence is a cautionary tale; others see it as a pathway for their regions to gain full sovereignty.

According to Bloomberg News, Somaliland's foreign minister, Mohamed Omar, says his government plans to take a "more aggressive policy toward the African Union in its efforts to gain international recognition from Somalia."

Nigeria Some compare Sudan to Nigeria, with its tensions between Muslim and Christians and between ethnic groups. In 1967, Nigeria defeated Biafran separatists fighting for an independent state for the Ibo ethnic group in the east. Recently, the president of the Nigeria Civil Rights Congress, Shehu Sani, called Sudan "a reference point for division and secession." "What's happening in Sudan is raising a lot of fears, especially in Nigeria, which is a colonial creation," said Sani in an article in the Guardian paper of Great Britain. "It was thought the defeat of Biafra had made division impossible, but Sudan is rekindling the thought."

An editorial in Nigeria's Guardian newspaper warns, "[Sudan] may provoke unwarranted secessionist tendencies across the continent" and serve as a wake-up call "to African leaders and authorities, including Nigeria, that the failure of governance has its price, including [national disintegration]." Other Nigerians disagree. Sully Abu is the director of media and publicity for the election campaign of President Goodluck Jonathan. Abu is also the publisher of the now-suspended New Age newspaper. He says Nigerians do not see themselves as divided by a largely Muslim north and Christian south, which he says is an assumption of many foreigners. "Here there is such complexity in tribes, regions and religion," he says, "that you don't find such neat demarcations as talk of a Muslim north or Christian south. The country is much more divided into states. People are more concerned about their particular localities rather than any big regional divides." Abu says people may want more local or regional autonomy, but they prefer to keep the country together. Yemen and Iraq The call for separation is also echoed throughout the Middle East and North Africa.

Algeria's foreign minister predicted "fatal repercussions" for Africa. Chad's president, Idriss Deby, warned of a domino effect – and "disaster" -- if countries with north-south tensions, like his own, follow Sudan's lead. Libyan leader Col. Moammar Gadhafi compares Sudan's split to a "contagious disease" that could be "the beginning of the crack in Africa's map." Analyst J. Peter Pham sees irony in Libya's concerns. Pham is the senior vice president of the New York-based think tank the National Committee on American Foreign Policy. "Historically, Gadhafi and Libya have been one of the biggest supporters of secessionist movements in Sudan," says Pham. "For many years, the [Sudan People's Liberation Army] and some Darfur rebel groups received support from Gadhafi. So [having helped them over the years], the colonel is relatively new to his anti-secessionism. "At same time Libya is [opposing secession], Libyan sovereign wealth funds are actually seeking investments in southern Sudan, so they are playing both sides against the center." Larbi Sadiki teaches in Britain at the University of Exeter's Department of Politics. He says separatists are active in Yemen and in Iraq. "The south of Yemen," says Sadiki, "is a place that until 1990 was a different state altogether, with a separate ideology, the emblems of a state -- and was an international actor in its own right. Of late, we've seen renewed yearnings for recreating that state. So, it's in the offing. The centralized [state] does not command a following in the south or from others [in other parts of the country.]"

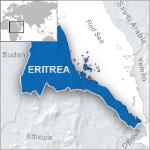

"For secession, the best candidate [in the Arab world] would be northern Iraq, Kurdistan. It approximates a quasi state, though without international recognition, and without demarcated and recognized borders. But, you have in place an entity working toward statehood. And, there are people with an aspiration to upgrade their autonomy into full-fledged [nationhood]." Analysts say there are plenty of areas in the Middle East and Africa that have had separatist movements, including the regions of Casamance in Senegal, Cabinda in Angola, Zanzibar in Tanzania and the disputed territory bordering Morocco, Western Sahara. But, it's not clear that any of these regions have the potential to actually separate. International backing Jon Temin is a senior program officer at the Center for Mediation and Conflict Resolution at the U.S. Institute of Peace. He says Sudan and Eritrea have what many states with separatist movements lack -- a long history of fighting for independence. Eritrea separated from Ethiopia in 1993. It had fought for independence for about 30 years. Separatists in Sudan fought for 50 years.

"Almost no country in Africa has the history of brutal civil war that Sudan does," says Temin. "They fought two civil wars that were among the longest in Africa that resulted in more than two million deaths. While other secessionist movements have certainly mounted significant armed resistance, nowhere else on the continent do we have this extremely bloody history that is important in recognizing the right to self- determination for the south." Temin says southern Sudan had something else most other liberation movements do not have -- extensive international support. A number of governments, including the United States, helped mediate the process of creating Sudan's five-year-old blueprint for power sharing and potential separation, the Comprehensive Peace Agreement. He says today the only other region in Africa to enjoy significant international support for its liberation struggle is Western Sahara, where the Polisario Front has been fighting for independence from Morocco. The United Nations granted the group official recognition 31 years ago. Regional security Analyst J. Peter Pham opposes recognition of Western Sahara. He says the international community should not recognize any secessionist movement that cannot stand on its own. He says Western Sahara has little more than 100,000 people and lacks natural and financial resources.

Pham says a country must also contribute to regional security, which he says Western Sahara does not do. For example, he says there's a "lack of freedom" in the refugee camps in Algeria run by the separatist Polisario Front. He says some of the Polisario's members are also involved in terrorist and criminal activities. In addition, he says the Polisario Front has played a role in keeping two regional powers, Morocco and Algeria, from cooperating on counterterrorism and other issues. Pham also says an independent Western Sahara would likely prove to be a "failed state," where the lack of governance would result in a safe haven for Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and other radical groups. Somaliland One region that does meet Pham's criteria is Somaliland, which declared its independence from Somalia in 1991. It has fully recognized offices in South Africa, Ethiopia and Ghana.

"[With] Somaliland," says Pham, "you have a state that is clearly viable. It's proven it by its 20 years existence. And, it adds to regional stability and security, keeping piracy away from its shores and helping (neighboring, landlocked) Ethiopia have access to [Somaliland's port Berbera] for imports/exports.... It is actually a bulwark against extremism in the region." Ivory Coast He also says northern Ivory Coast shares trade and cultural patterns with countries to the north, giving it more in common with them than with the southern part of the country, which produces nearly all of Ivory Coast's cocoa. In much the same way, he says southern Sudan is closely linked geographically and economically to Kenya and Uganda. And he says the eastern region of DRC has more in common with its neighbors in East Africa than with the capital, Kinshasa, in the west. Pham says European states have shown that power can be decentralized to smaller regions -- like Catalonia in Spain and Scotland in Britain. This, even as market forces push for greater integration. Dr. Larbi Sadiki of the University of Exeter says many Arab and other governments do not favor decentralization. Instead, they use force to impose unity. He says that would not be necessary if they adopted legal safeguards to protect minorities so they would not feel they had to secede in order to protect themselves.

Analyst Jon Temin says both Eritrea and Southern Sudan had bloody and decades long wars for independence

Analyst Jon Temin says both Eritrea and Southern Sudan had bloody and decades long wars for independence Western Sahara separatists enjoy a degree of international support, but some question if it can stand alone, or contribute to regional security

Western Sahara separatists enjoy a degree of international support, but some question if it can stand alone, or contribute to regional security

Somaliland leaders say they're inspired by secession of Southern Sudan