22 June 2010

Photo: Courtesy United Tribes Technical College

The buildings used to house internees are still standing today, and serve as classrooms and dorms for United Tribes Technical College.

North Dakota is a land of broad, open prairie known for its Native American heritage, the travels of explorers Lewis and Clark and record snow and cold.

But there are parts of North Dakota's past that many are unaware of.

During World War II, it was home to an internment camp for aliens, as well as American citizens the government considered a threat to the nation's security.

Courtesy United Tribes Technical College

Established as a military post in 1895, Fort Lincoln was converted into a detention center in 1941.Painful past

Dennis Neuman is the public information director for United Tribes Technical College.

Before the college was established in 1969, this site was a U.S. Army post known as Fort Lincoln.

"They turned this fort into a camp for Germans and German alien citizens, German nationals and Japanese and Japanese-American citizens, and some other nationalities," says Neuman.

On an overcast spring day, 60 people - former internees and descendants of internees - gathered at the college for a conference to recall those times, and to create a memorial to those who lived through it.

Courtesy United Tribes Technical College

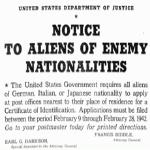

In 1942, the Department of Justice issued notices advising aliens to register for Certificates of Identification at their local post office.Recording history

College president David Gipp sees a significant parallel between what camp internees endured and what the many Native American tribes represented at the college suffered at the hands of the federal government.

"We not only lost our land, but we lost a lot of our fundamentals in terms of the ability to move across the land, the ability to express ourselves, our traditional forms of government," says Gipp, who believes it's imperative for United Tribes Technical College to support this preservation of the past.

"And it's important to record this for history. Especially people that don't realize that here was a place on the high northern plains, the high prairie, where this kind of thing occurred."

"This kind of thing" included the incarceration of 1,800 Japanese, 1,500 Germans, as well as smaller numbers of Italians and other Europeans at Fort Lincoln during the war years, under the Alien Enemy Control Program.

Ebel Family Collection

Max Ebel, far right, boarding the SS New York in May 1937, bound for New York City.Internment camp

Karen Ebel's father emigrated to the U.S. in 1937 from Germany to flee the increasingly oppressive Nazi state, and began to take the steps necessary to become a U.S. citizen. The process took several years.

"The day that he actually filed his citizenship papers was December 5th," Ebel says, "and, of course, we all know what happened on December 7, 1941. So, the process sort of came to a screeching halt at that point."

After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the U.S. declared war on Japan and Germany. Nine months later, Ebel's father was arrested. He remained a prisoner in his newly-adopted country for most of the war.

Like family members of many of the internees, Ebel didn't learn about that chapter of her father's life for many years. She says anger doesn't begin to describe her feelings when he told her the story. "Hurt and betrayal. I guess maybe a lot of the same emotions that my father felt because of what happened to him."

That was the story of tens of thousands of other legal aliens, as well as thousands of Latin Americans of German and Japanese ancestry, who were brought to the U.S. at the request of the Roosevelt Administration.

VOA - J. Kent

Arthur Kazuya Ogami attended the Ft. Lincoln Memorial conference at United Tribes Technical College.No guarantee

American citizenship was no guarantee of safety, though.

The U.S. sent 120,000 Japanese-Americans to detention camps. Most of them were on the West coast. But Arthur Kazuya Ogami was among 650 Japanese-Americans at Fort Lincoln who were coerced into renouncing their American citizenship and were later deported to Japan.

Ogami regained his U.S. citizenship in 1952 and returned the following year. He recalls his emotion as he stepped back onto U.S. soil.

"It felt great," he says, as his voice quivers. "I thought I'd never be able to come back."

Ogami says he holds no grudge, but the hurt lingers. "It's still here. And the memory's here. And I want those memories recorded... documented... go into the classrooms. This is why I'm willing to talk."

The National Park Service has awarded grants to preserve and interpret more than 50 historic locations across the country where internees like Arthur Ogami and Max Ebel were held.

The former site of Fort Lincoln is among them, and the conference participants here hope to have a memorial in place within the next five years.