Washington

26 February 2009

|

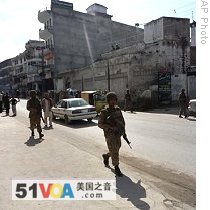

| Pakistani army troops patrol on a road in Mingora, the main town of the Swat Valley, 24 Feb 2009 |

According to analysts, Pakistan is one of the most prominent examples of a nation where economic pressures are feeding unrest and threatening a wobbly government.

In recent Congressional testimony, Director of National Intelligence Dennis Blair said the burgeoning world financial crisis is highlighting the linkages between insurgency and economic instability there. "The government is losing authority in the north and west. And even in the more developed parts of the country, mounting economic hardships and frustration over poor governance have given rise to greater radicalization," he said.

Growth has stalled in Pakistan, while prices of food and fuel are up. Inflation, while down slightly from last year, still hovers at around 20%. Shuja Nawaz, director of the South Asia Center at the Atlantic Council, says such ingredients are a classic recipe for radicalization.

"Well, I don't know if they're paying much attention to the economic news, but the Taliban know only that when the government is unable to deliver services, and when there is unhappiness among the general population because food prices have gone up tremendously, gasoline is not available, electricity shortages are rampant, that it is much easier to convince the people that the Taliban have the solution rather than the government," he said.

In a new report, the Atlantic Council says time is running out for Pakistan, and calls for an immediate infusion of an additional $4 billion to $5 billion in aid with similar amounts next year. Nawaz says the aid is critical to Pakistan's survival. "It has to be propped up in the sense that you have to stop the slide. And if you don't do that then everything else really falls by the wayside," he said.

Pakistan has already received nearly $12 billion in aid from the United States since 2001, the bulk of it for counterterrorism. It obtained a $7.6 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund last year and is reported to be seeking an additional $4.5 billion.

International Crisis Group senior vice-president Mark Schneider says non-military aid should be an integral part of the U.S. counterinsurgency strategy against al-Qaida and Taliban fighters taking sanctuary inside Pakistan's border areas.

"The fundamental objective of the counterinsurgency strategy when you're working with a government is to strengthen that government's capability to broaden its legitimacy. And it broadens its legitimacy by governing, extending services, creating jobs, providing economic opportunity for the population, and providing some kind of, as I said, citizen security and rule of law," he said.

Pakistan has had a civilian government for only a year. President Asif Ali Zardari and his Pakistan Peoples' Party came to power in elections last February after nine years of military rule under General Pervez Musharraf. But the government is perceived as struggling to get a handle on battling Islamic militancy even as it deals with the economic crisis.

Pakistani Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gilani has said that Pakistan wants "trade not aid." But Mark Schneider says Pakistan needs both to survive.

"What you really need is trade and aid because trade doesn't do anything with respect to building a police force or training judges or training teachers. That comes about from government services. And so you need both aid to help strengthen those government agencies, and you need trade to permit the expansion of an economy," he said.

Some analysts believe the combination of insurgency and ineffectual governance may prompt the military to step back into the political arena again, as it has done for more than half of Pakistan's nearly 62-year history.