Addis Ababa

07 April 2009

|

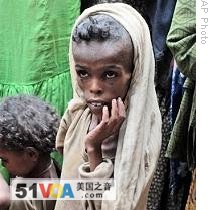

| An Ethiopian child waits for food aid (file photo) |

"As you know Ethiopia has one of the highest child mortality rates, which is about 120 per thousand live births," said Dr. Zelalem Demeke, the medical director of Addis Ababa's Bole Clinic as he gives a tour to a group of visiting foreign lawmakers. He frankly admits the challenge is enormous.

But while Ethiopia's childbirth-related death toll is third highest in the world, it is not much worse than that in many other impoverished countries. The World health Organization estimates 99 percent of maternal, newborn and child deaths occur in countries at the bottom end of the economic scale.

Health Minister Tewodros Adhanon says countries like Ethiopia never have enough doctors and trained health professionals to go around. So they have come up with the next best thing, an army of community level people with enough training to handle basic emergencies, and to get professional help quickly when more expertise is needed.

He says the strategy is beginning to pay off. "We are starting to see some results. The encouraging results means we can build more on the strategy we have designed," he said.

Tewodros says it has been less than 20 years since more than one in every 100 Ethiopian mothers died in childbirth. He says current figures are still not good, but deaths have been reduced by a third.

Barbara Contini is a member of Italy's delegation to the Inter-Parliamentary Union conference. She is a senator, but earlier she spent 23 years building health facilities in developing countries. She worked in Ethiopia in 1996. She tells fellow lawmakers investing in health care in Africa is good for donors as well as recipients.

"I always tell in Italy that this is an opportunity, because if we stay better in Africa, then we will stay better in Europe," she said.

Dr. Flavia Bustreo of the World Health Organization is accompanying the parliamentarians on their clinic tour. She says early intervention in developing countries could prevent nearly three quarters of maternal deaths, and two-thirds of child deaths.

"So the child is seen and is treated for a current illness, but also for the underlying problems he may have, for example malnutrition, which in the Horn of Africa is very prevalent. And also the mother who is accompanying the child is examined," she said.

It is too early to tell if Ethiopia's strategy is the answer. But given current financial realities, it remains a hope for correcting the vast inequities in maternal and child health between rich countries and poor.