Nairobi

30 July 2009

A fight to save a sensitive Kenyan forest is threatening to derail one of the major tribal alliances within Kenya's government. But this time a frustrated Kenyan population is running out of patience with political power plays. Environmentalists say nothing less than the very future of the country is at stake.

Kenya's Rift Valley gathers attention

|

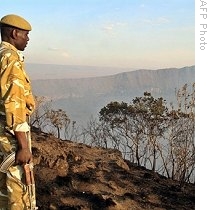

| A Kenya Wildlife Service, KWS, ranger inspects a section of Mt. Longonot National park, near the lakeside town of Naivasha in the Kenyan Rift Valley (File) |

As the largest water catchment area in the country, the Mau supports an ecosystem stretching across East Africa. The forest is the source of 12 rivers, including the famous Mara River, responsible for Kenya's biggest tourist attraction and home to one of the world's seven natural wonders of the world.

But lax conservation enforcement and political nepotism have contributed to the systematic destruction of the forest. Politicians grabbed pieces of the land or gave it away to fellow tribesmen, who often then sold the land to poor settlers who have slowly pushed back the boundaries of the forest.

Government to address Mau Forest issue

Led by Prime Minister Raila Odinga, Kenya's government appears finally to have found the political will to address the Mau issue. With a severe drought on Kenyans' minds and amidst growing pleas from environmentalists, the timing might finally be ripe for action.

But with a quarter of the forest already cleared as lumber and charcoal to make way for farming, environmentalists say that time is not on Kenya's side.

Charles Peter Mwangi, a Mau Forest specialist for the Kenyan environmental group Green Belt Movement, says that the region's loss of water due to the deforestation is already at an emergency level.

"Something needs to be done immediately. People need to get out. The question of resettlement can actually be handled much later," said Mwangi. "But we need first of all to tell people to get out, outside the forest. Now they can negotiate with the government whether they will be compensated or not, but first of all they need to be outside the forest so we can start rehabilitation work."

Former regimes exploited forests

In many ways, Kenya is still suffering the sins of regimes past. Macharia Munene, a local history professor, says that former president Daniel Arap Moi, a member of the Kalenjin tribe which populates much of the Rift Valley, used his near-dictatorial powers to exploit the forest for his and his friends' personal gain.

"In general there was a lot of recklessness at the government level, and people in the top echelon were simply grabbing whatever they can get," said Munene. "The bigwigs gave themselves, not just the Mau, but a lot of the forest areas, and then they would resell some of it. So it has been a systematic process."

The question of compensation has been a crucial sticking point to the negotiations between Mr. Odinga and Rift Valley parliamentarians, who are a key part of the shaky ethnic coalition behind the political party Mr. Odinga leads. Growing discontent between the two sides have led some Mau area leaders to threaten to pull out of the party.

Both sides claim to agree that only those small scale farmers who paid for title deeds should be compensated. But sifting through the claims of legitimate versus illegitimate title owners will likely prove to be an arduous, and potentially explosive, task.

To many Kenyans, though, the complaints raised by the Kalenjin politicians have little to do with the poor they claim to be helping and everything to do with political opportunism on an issue many of their countrymen view as far too serious for use in populist games.

Worse, some of the area leaders are suspected of being major beneficiaries of the illicit land grabbing. In a move to put more pressure on the local politicians stalling government action, Mr. Odinga has released the names of identified major land owners in the forest. The list includes two ministers of parliament and a number of politically-connected companies.

According to Mwangi, the region's drought is not unrelated to the forest's destruction. The subsequent shifts in the local micro-climate has meant that areas that used to receive plentiful rainfall can no longer expect much rain.

Mau is important to Kenya and other countries

The Mau, with its 12 rivers, is crucial not just for Kenya. Lake Natron in Tanzania, a major breeding ground for flamingoes and a significant tourist draw, is sourced from a Mau river. Lake Victoria, which supports the livelihood of fisherman in a number of East African countries and feeds into the Nile River, is also a recipient of much of the Mau precipitation.

Mwangi asserts that the tide of destruction is not irreversible. If the settlers are evicted from the forest area and resettled elsewhere, then he says a renewed conservation effort can begin to expand the forest back to its original boundaries.

It is possible to revoke the situation, because all we need to do is secure the boundaries of the forest and do enrichment planting. And therefore we can actually be able to reclaim our forest back. But political goodwill has to be there, politicians have to agree to agree.

With fellow members of parliament beginning to publicly heckle the Rift Valley representatives for their Mau stance, the prime minister seems to have secured the political momentum for the moment. Local Kenyan media has been strongly supportive of the government's new found resolve to tackle the Mau issue.

Yet many obstacles remain. Even Mr. Odinga does not seem to know where the government will find the money to pay for the settlers' compensation. And it is unclear if settlers will voluntarily leave without the use of force.

For the estimated 5.5 million people who depend on the Mau as a water source, however, more government stalling is not the option they are hoping for.