Liquica, East Timor

07 September 2009

Ten years ago, East Timor voted to end Indonesian rule in a referendum that was marred by violence and destruction. Many victims of the violence say they want those who carried it out brought to justice, but the East Timor government urges its citizens to forget the past.

Ten years ago, East Timor voted to end Indonesian rule in a referendum that was marred by violence and destruction. Many victims of the violence say they want those who carried it out brought to justice, but the East Timor government urges its citizens to forget the past. Three men are gathered in a small bamboo shack. They chant incantations to call the soul of Fernando Da Costa back to his ancestors' home.

Jose Da Costa, Fernando's father, explains that he has been looking for the body of his 28-years-old son for 10 years but never found his remains.

Haunted by the past

The East Timorese believe a curse plagues the families of people who die without a proper burial, so this ceremony is to symbolically put Fernando's soul to rest, and bring peace to his bereaved relatives.

But Fernando is not the only ghost roaming around Liquiça village. It is a community haunted by its past.

In April 1999, Indonesian soldiers and Timorese militias stormed into the village church, where 2,000 residents had sought refuge. They killed 30 to 100 people and dumped most of the bodies in unknown locations. It was a few months before East Timor's referendum for independence, and Indonesian forces were intent on intimidating potential pro-independence voters.

Demand for justice

Jose Nunes Serrao was one of the ones who escaped. He still carries a reminder of that day: a fat scar that runs from the middle of his neck to the top of his cheek, where the machete of a militiaman almost severed his head.

Jose says that he wants to see those responsible for his ordeal brought to justice - not only the soldiers, but especially the top leaders of the Indonesian army who ordered the massacre. Otherwise, he says, there is no way to prevent them from doing this again to his children or his grandchildren.

But 10 years later, he fears those responsible will never be brought to justice.

International politics blamed

The United Nation's Serious Crimes Unit has indicted more than 390 people for crimes against humanity in East Timor. Only 87 have stood trial; most still live freely in Indonesia, out of reach of East Timor tribunals. And of the 84 people convicted, only one remains in prison. All the others have been granted presidential pardons.

Charlie Scheiner is an analyst from Lao Hamutuk, a rights organization that monitors the development of East Timor's social and civic institutions. He says international politics explain why so few have been tried for rights abuses.

"Timor Leste [East Timor] cannot survive without good relations with Indonesia," Scheiner said. "Not because Indonesia is going to invade, but because last year, for example, 40 percent of what this country imported came from Indonesia. Drinking water comes from Indonesia; instant noodles come from Indonesia; things that everybody uses. So the leaders here are prioritizing friendship."

Forgive and forget

East Timor's leaders, many of them former rebels who fought Indonesia, see reconciliation with the former occupier as more crucial for the future of the country than judicial action to bury the ghosts of past violence. They ask their countrymen to "forgive and forget" past crimes.

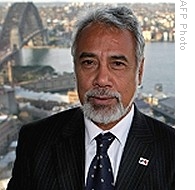

|

| East Timorese President Xanana Gusmao (File) |

But the policy does not satisfy some victims of Indonesian atrocities, such as Liza Da Silva Dos Santos, another survivor of the Liquiça massacre.

She says they have shed their blood for independence, so that their leaders can now sit in their government offices in Dili. She says if she had known this would happen, she would have told her husband not to side with the independence movement. At least he would still be alive and they could be happy together.

Legal system flawed

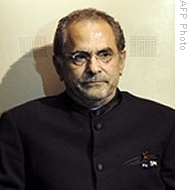

|

| Jose Ramos-Horta (File) |

"The only hope now is broader interpretation and evolution in international law, which is moving in the direction of universal jurisdiction for crimes against humanity and war crimes," Gentile said. "And that's the duty of everyone who believes in justice and in deterring the gravest and most serious types of crimes that the United Nations was partially set up to prevent after the Second World War, and continues to fail to prevent."

For now, it appears unlikely that the East Timor government's policy will change. Amnesty International recently called for the creation of an international tribunal to try crimes against humanity in East Timor. But the country's president, Nobel Peace Prize winner Jose Ramos Horta, rejects that idea.