May 14,2013

Researchers are developing new techniques to find hidden graves. They say it would help locate the remains of a lone murder victim or the mass graves of victims of war. The research has been prese nted at the Meeting of the Americas in Cancun, Mexico, co-sponsored by the American Geophysical Union.

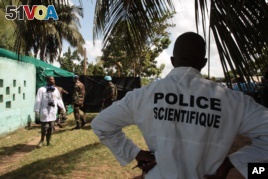

Forensic scientists and doctors prepare for the exhumation of a mass grave site on the grounds of a mosque, in the Yopougon district of Abidjan, Ivory Coast, April 4, 2013.

Jamie Pringle Said, “There are thousands of missing people around the world that could have been tortured and killed and buried in clandestine graves.” Pringle is a lecturer in geoscience at Britain’s Keele University.

“It’s important for families obviously to find their relatives – to give them closure – so they can find out what happened to them and give them someone to bury. But of course also it’s really difficult to get a successful criminal conviction without a body. It does happen, but normally it’s more unusual. You get charged with something like illegal deposition of a body or preventing a proper funeral, things like that,” he said.

He said that there have been a number of missing child cases in Britain where this has happened. It can be just as hard to locate mass graves of people who disappeared during wars.

“[In] some of the Africa conflicts obviously it’s very chaotic. The perpetrators don’t obviously leave a map of where they’ve deposited people. Could be isolated graves or mass graves in a variety of environments and that can be quite difficult to find, I think, especially if there’s some significant area to search and you have limited resources. It’s really hard to be honest,” he said.

Pringle’s colleague, Carlos Molina of the National University of Colombia, will test the techniques in the South American country. Many people there have gone missing in drug and other crime related violence.

Molina not only wants to be able to find bodies, but evidence that can be used in criminal prosecutions, such as the time of death. To do so, he’ll create simulated gravesites based on sites that have been found in the past.

Pringle said, “He’ll create some burials using normally animal cadavers rather than humans. Fill it in again and then basically survey them over set periods of time to see what technique works best and does that change over time. But obviously over time that gets vegetated again and often you get people called forensic botanists. They look at vegetation changes. It may be different plants might grow there or they might grow better perhaps if they’re well fertilized to be a bit grizzly about it.”

The sites would be surveyed every eight days during the first month, every 15 days in the second and third months and then once a month for the next 15 months. Scientists will use instruments such as ground penetrating radar in their work.

Pringle said that there’s a specific workflow when trying to locate hidden graves.

“Normal work flow is you go from the big scale -- some remote sensing methods, some old aerial photos or modern ones, in fact, or some sort of nonvisible wavelength data to see if you can see where things might have been disturbed. And then you say well those areas look interesting. And then, ideally collect some data over there and see if you can see if there’s anything buried there.”

Forensic geophysicists from around the world, he said, are collaborating to solve disappearances stemming from conflicts.

“The Balkan civil wars from the 1990s, trying to find some of those graves in mountainous areas in the former Yugoslavia, for example. I have colleagues in Spain looking for some of these civil war mass graves, which is a little contentious over there. There are some people who want to find their relatives and other people – maybe the perpetrators or their colleagues – [who] don’t want them to find them. So there are colleagues working in Queens University in Belfast, they’re trying to find some of these victims from the 1970s and 80s in Northern Ireland,” he said.

It can be a very long, slow and painstaking process.

Pringle said he’s currently helping to find the graves of some nomadic groups in West Africa before mining operations begin.