Houston

18 February 2009

For the past 2.5 years, two agriculture experts from the U.S. state of Texas have been working in remote areas of Afghanistan to help nomadic herders better manage their sheep, goats and cattle, and to better deal with ever-changing environmental conditions. The project has also helped peacefully resolve conflicts over grazing rights on the Afghan range.

|

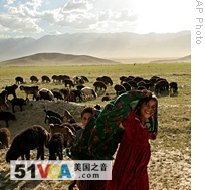

| A Kuchi shepherd girl and a boy guide their flock in the pasturelands of Shomali Plains, north of Kabul (2005 photo) |

"They are essentially survivalists," said Michael Jacobs. "And because of this, they are pretty aggressive; they come off that way. They are not afraid to tell you what they think. But in the end, that actually helps you because you do not waste time doing things that they are not interested in doing or that they do not think is going to work."

What Jacobs and colleague Catherine Schloeder are trying to do is introduce the Kuchi to modern ways of managing their herds and ways of using high technology to find the best grazing areas at any given time.

Professor Schloeder says she has also learned a lot from the Kuchi about living together in a challenging environment.

"I find that I benefit from this experience as well, in that I am a better person," said Schloeder. "I take away so much from these people in how to better communicate with people, how to live with people."

The head of Texas A&M University's Department of Ecosystem Science and Management, Steven Whisenant, says these two experts, who have also done extensive work in Africa, bring a lot of experience gained in Texas to what may at first glance seem to be a very different landscape in Afghanistan.

"There are some similarities with Texas and then there are some very significant differences," said Whisenant. "Our pastoralists, our ranchers, tend not to be nomadic. The semi-arid rangeland is quite similar. To our experts in rangeland management, livestock management, that expertise has global relevance."

Part of what the Texas experts do in Afghanistan involves tracking weather information from U.S. satellites to determine where the Kuchi should move their herds for better grazing. But for a people with a literacy rate around four percent, Whisenant says such information can be difficult to comprehend.

"It has to be presented in a way that is useful to the Kuchi people," he said. "But in the process of doing that, it sort of opens their eyes to the idea that there is a bigger world out there and there is information available that they may never have imagined that is useful to them."

Technology already available to some Kuchi has played a role in efforts to resolve conflicts over grazing land peacefully. In the past, most of these conflicts in Afghanistan have been resolved through Islamic courts composed of local people who generally rule against the nomads.

But the two Texas professors, working with other experts from non-governmental organizations, have encouraged the Kuchi and the locals to use a technology some of them already had in their hands.

"They began exchanging cellular phone numbers," said Whisenant. "The Kuchis are pastoralists and nomadic, but many of them have cell phones. So now, when they move into an area, they call people on their cell phones."

Whisenant says some local communities allow Kuchi representation in local courts so that disputes can be resolved fairly. The professors from Texas A&M University work in Afghanistan in a program funded in part by the U.S. Agency for International Development and work in close coordination with Afghan government agencies as well.