Islamabad

25 February 2009

This week top Pakistani, Afghan and U.S. officials are meeting in Washington to discuss how to counter al-Qaida and Taliban fighters, who now threaten both U.S.-backed governments in the region. In Pakistan, officials are moving forward with a controversial peace agreement with one group of Taliban militants who effectively took over Swat valley, a well-known tourist retreat less than 160 kilometers from the capital.

|

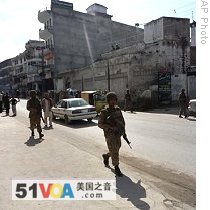

| Pakistani army troops patrol on a road in Mingora, the main town of the Swat Valley, 24 Feb 2009 |

Following an on-again, off-again, 18-month war against the Swat Taliban, locals now blame both the military and the Taliban for killing hundreds, displacing thousands and destroying the valley's economy.

One resident says many people in Swat cite the destruction caused by both sides as evidence they are secretly working together.

"There is this perception that the Taliban and forces - they are one people," said the resident.

Another man, who also declined to be identified because of fear of reprisals, said at times it felt as if locals were being attacked first by the Taliban and then by the military.

"Ninety-five percent of people were thinking like that," he said. "They were thinking the army is the A team and the Taliban is the B team."

Locals also cite the army's inability to kill or capture any Swat Taliban leaders, despite the government's firm control in the area just a few years ago as evidence the military has, at best, waged a half-hearted campaign.

Army spokesman General Athar Abbas rejects allegations the Taliban and army are working together, saying nearly 200 Pakistani troops have been killed in Swat. But he admits the military has failed to hit Swat Taliban leader Maulana Fazlulla, or any of his top commanders.

"You're right, maybe, the top leadership has not been engaged or targeted in Swat. Remember the militant leadership is the center of gravity of militancy," said Abbas. "And it doesn't expose itself - it always moves around with a shroud around it. And therefore it is difficult directly to hit that."

While militant leaders in Swat are rarely seen, they are frequently heard. Illegal Taliban radio stations broadcast daily programming from some 30 towers across the valley as well as mobile transmitters on vehicles. The army has tried to jam the signals, but says it has just three devices that only cover a limited area.

The broadcasts have a large audience - many residents say they must tune in, to hear what the Taliban is planning. Every night, a spokesman reads from the Koran, announces policies and issues threats.

A Swat Taliban spokesman Shah Duran on a recent broadcast calls for the death of journalists accused of misreporting the Swat conflict. He says reporters should be extra careful, because the Taliban is powerful.

In recounting the army's failure to pacify Swat, spokesman Abbas cites a crucial period last spring - when the military offensive was halted while the provincial government tried to negotiate a truce. The general says the Taliban took advantage of the lull in fighting to behead and beat locals who had opposed them. He says when the army returned, local support had vanished.

"We had lost our connections, our informers, our support from the public. You had to separate the militants from the civilians - they had mixed into the population and it became difficult for the military without having informers to separate them. And that started resulting in collateral damage of death, destruction and displacement," added Abbas.

Such counter-insurgency problems are well-known to U.S. commanders who have struggled with similar scenarios in Iraq and Afghanistan. A group of American military advisers is now in Pakistan, helping to train several hundred Pakistani forces in counter-insurgency tactics.

|

| Richard Holbrooke (file) |

But a former governor of Pakistan's North West Frontier Province, Khalid Aziz, says that will be difficult, because Pakistan's military is still focused on its long-time rival India.

"The threat perception from the Pakistan point of view is imminent threat from the Indian direction. And that's why the deployment of the forces takes this configuration - the threat seems to be more from the east than from the west," said Aziz.

Despite lingering tensions with India over November's Mumbai terrorist attacks, President Asif Zardari said earlier this month that Pakistan is now fighting for its survival against a Taliban that is trying to take over.

But the government's most recent strategy to deal with the militants in Swat by halting military operations and trying to negotiate a peace deal has drawn concern from U.S. officials.

The deals call for fighters to lay down their arms in exchange for establishing courts that proceed in accordance with Islamic law.

Critics say officials are further undermining the government's authority and ceding more territory to the Taliban. But locals, such as this man who lives near Swat's main city Mingora, worry the agreement's failure, and a resumption of hostilities, will only lead to more suffering.

"It it fails - I am worried about it. I think the situation will be very, very, very bad and the Swat people will face more difficulties," he said.

Some Pakistani analysts agree. Khalid Aziz says he is hopeful about the agreement, but he says that regardless of the outcome, Pakistan's government must improve its ability to clear and control Taliban-held territory, without losing public support.