Colombo

25 February 2009

|

| Rebels examine their weapons in this handout picture released by The Liberation Tigers for Tamil Eeelam (LTTE) website Tamilnet (file photo) |

Even here, at one of Colombo's five-star hotels on the white-sand beach of the Indian Ocean, it is hard to tell that the country is embroiled in a war - one of Asia's longest-running. Still, there are signs. For one, there is a noticeable lack of guests.

This hotel, like others in the capital, is seeing a steep drop-off in new tourist arrivals. That is not good news for Sri Lanka's $240-million-a-year tourism industry, among the economic sectors hardest hit by the recent fighting between government troops and ethnic Tamil rebels who have been fighting for a separate Tamil homeland.

But tourism is not the only sector to take a beating. The garment industry is laying off workers, as orders from abroad are postponed or canceled. Prices are falling for three of Sri Lanka's most lucrative exports: rubber, precious stones and tea. Remittances from Sri Lankans living abroad, widely seen as a financial safety net for many Sri Lankan families, are dwindling.

|

| Kishu Gomes is a business leader in Colombo, and former chairman of the American Chamber of Commerce in Sri Lanka |

"People, in general, have been suffering as a result of the ongoing conflict, where the government has had to spend a lot of money battling the situation. And, in that, it was obviously a big burden on the country's economy," said Gomes.

One of the biggest burdens on Sri Lanka's economy is its massive military spending, seen as necessary expense for defending itself against the Tamil Tiger rebels, classified by the United States and other countries as a terrorists. Military spending accounts for about five percent of Sri Lanka's $30-billion-a-year economy - nearly twice the percentage of its regional neighbors India and Pakistan.

Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu is the director for the nonpartisan Center for Policy Alternatives. He says that, with the war's end in sight, many Sri Lankans expect a situation similar to the 2002 cease-fire or the 2004 tsunami, which brought peace - albeit briefly - and a huge increase in humanitarian and reconstruction aid.

"But what does not figure into that, of course, is that there is not a heck of a lot of money around in the rest of the world anymore. And, so, that is going to be a serious problem," said Saravanamuttu.

|

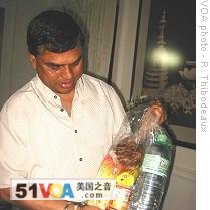

| Basil Rajapaksa, brother and top advisor to Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa, displays some of food aid handed out in camps for those displaced by war |

"We have cultivated a 132,000 acres of [rice] paddy land that had been abandoned more than five to 20 years. And, now they have started harvesting and it will increase the paddy production of the country and the growth rate itself will be increased by two to three percent. So, all this benefit will go to the people," said Rajapaksa.

He says with the war ended, some of the money spent on defense could go toward building new roads and other infrastructure projects that support businesses and farmers.

Gomes says he, too, is hopeful that the country will recover. He says just about anything would be better than the status quo.

"I hope that, over the next 12 months' time - with being able to achieve total peace and the country becoming a more productive place - we will be able to probably find the right opportunities elsewhere in the world to keep the revenue ticking. And, then [we] hope the global economic crisis will end, and with that, we look at the five- to 10-year horizon and it can only be better than what it is today," said Gomes.

Still, analysts and diplomats here say the nation's leaders must address the root cause of the war - discrimination against the island's minority Tamil population at the hands of its Sinhala majority - if they hope to achieve a prosperous future for this nation of 21 million people.