Brent

15 September 2009

Human rights advocates say the recent conviction of a former paramilitary officer on charges of orchestrating the forced disappearance of six ethnic Mayan villagers in the mid-1980s signals the country might be ready to deal with its legacy of human rights violations.

|

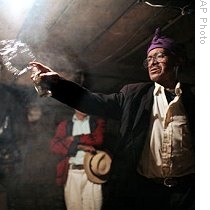

| Mayan spiritual guide sprinkles alcohol on the coffins of six people who were killed in the 1981 massacre of 79 people by the Guatemalan Army at a mass burial in Cocop, Guatemala (File Photo - 9 Jun 2008) |

But the history of this region, a bastion of Mayan culture and resistance to the governments that ruled Guatemala in the mid-1980s, make the area an epicenter of the ongoing search for reconciliation over what human rights groups call widespread genocide perpetrated largely against the country's indigenous people more than two decades ago.

Guatemalan civil rights lawyer Mario Minera says the six peasant farmers who disappeared from Choatalum and presumably were killed during the early-1980s are only a fraction of the more than 600 unresolved documented cases. Most of the killings acknowledged in Guatemalan and international courts took place during the presidential administrations of military rulers Jose Efrain Rios Montt and Oscar Humberto Mejia Victores between 1982 and 1986.

A U.N.-backed truth commission found that about 200,000 people were killed and more than 40,000 disappeared during Guatemala's 36-year Civil War that ended in 1996. The killings peaked in the mid-1980s. Many of the victims were ethnic Mayans.

Attorney Mario Minera says that for years, the perpetrators of the crimes lived with impunity, under what he and other human rights activists describe as Guatemalan state reluctance to investigate the alleged crimes of those in power and, in some cases, are still active in the government.

But that began to change earlier this year, when a Guatemalan court ruled that crimes involving the "forced disappearance" of Guatemalans missing since the 1980s could be considered active cases and not subject to a statute of limitations.

Attorney Mario Minera says the decision opened the way for the prosecution of individuals suspected of coordinating the atrocities.

The first to be convicted under the new ruling was former military collaborator Felipe Cusanero, a civilian commissioner accused of six cases of forced disappearance of members of the Choatalum community. Earlier this month, Cusanero was sentenced to 150 years in jail for his part in those disappearances.

Human rights activists worldwide have hailed the sentence as a milestone in the fight for reconciliation for the families of victims in Guatemala.

"There are other cases where convictions are very likely in the imminent future," said Attorney Andrew Hudson of the New York-based organization, Human Rights First. "So I think this is important on a number of levels in that it shows that people can be prosecuted in Guatemala. And I think it will really open the doors for justice in many other cases in Guatemala as well."

Rights advocates in Guatemala say the case is the first of several being processed in the courts.

While experts agree that the Cusanero case is a big step forward, Hudson says further action will be needed if Guatemala is to overcome its history of impunity for human rights violators and move toward reconciliation.

"Through these emblematic cases you can start to reinstate the rule of law. You can start to try and heal the wounds of the civil war," said Hudson. "Mayan villages cannot move forward if they are living with the person who killed and massacred their entire village. It is just not possible to have reconciliation, in my opinion, without holding some of the worst perpetrators of human rights abuses to justice."

Many experts say impunity for those associated with atrocities has not only hampered efforts at justice for the victims, but also has filtered through Guatemalan society, leading to a culture of violence and disenfranchisement.

Large groups of the country's population, including women, youths and indigenous people, are still frequently the victims of basic human rights violations, says Sebastian Elgueta of Amnesty International.

"To view the current public security crisis and current level of violence in a vacuum or de-contextualized does not really work very well to understand the reality of Guatemala. The institutions in Guatemala have not, for years, actually exercised effective investigation and prosecution into crimes, because during the conflict they could not. It is a question of rebuilding these institutions."

In late 2007, the United Nations and the government of Guatemala established an independent body, the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala, to investigate continuing crimes against human rights advocates, and uphold the rule of law.